Lure Reward Training

By. Dr. Ian Dunbar – Courtesy of www.dogstardaily.com

In pet dog training, there is an endless quest for the quickest, easiest, most enjoyable and most expedient route to produce equipment-free and gizmo-free response reliability. The choice of training technique will have a huge influence on “time and trials to criterion.” As the quickest, and one of the simplest of all training techniques, lure/reward training is the technique of choice for most owners to teach their dog basic manners. For behavior modification and temperament training, food lure/reward training should be mandatory. There is extreme urgency to prevent and resolve behavior problems. Simple behavior problems, such as housesoiling, destructive chewing, and excessive barking, kill dogs. Time is of the essence. Similarly, biting, fighting, and fearful dogs are hardly happy, or safe to be around, and so there is simply no time to mess around with time-consuming techniques. We must resolve the dogs’ problems, relieve their chronic, yet acute, stress levels, and improve their quality of life using the most time-efficient methods available.

Other techniques are championed in other specialist training fields, wherein the syllabus is finite and the trainer knows the rules and questions (criteria) before the examination and especially, when time is not an issue—knowledgeable, experienced, and dedicated handlers will train for hours to perfect a desired behavior. However, pet dog training differs markedly from teaching competition or working dogs. With pet dog training, the questions are unknown and the syllabus is infinite — comprising all aspects of a dog’s (and owner’s) behavior, temperament, and training. But the most important difference by far — by and large owners are not dog trainers; they seldom have a trainer’s education, experience, or expertise.

Trainers should never underestimate their own expertise. Characteristically, techniques that we recommend for owners to train their dogs are entirely different (easier, quicker, and less complicated) than techniques that we might use to train our dogs.

In pet dog training, the two most expedient techniques are Lure/Reward Training and All-or- None Reward Training. This article describes a comprehensive lure/reward training program, which comprises five stages:

The first three steps focus on establishing response reliability and are all-important in all fields of dog training. The last two steps — for refining precision and for protecting precision and reliability — are primarily for obedience, working, and demo dogs and will only be summarized in this article.

I. Teaching The Dog What We Want Him To Do

Stage I involves completely phasing out food lures as they are first replaced by hand signals (hand lures) and then eventually, by requests (verbal lures).

Given the prospect of the plethora of rewarding consequences for appropriate behavior, most dogs would gladly respect our wishes and follow our instructions, if only they could understand what we were asking. In a sense, Stage I involves teaching dogs ESL—English as a Second Language — teaching dogs the meaning of the human words that we use for instructions. Dogs need to be taught words for their body actions (Sit, Down, Stand, etc.), and activities (Go Play, Fetch, Tug, etc.), and for items (Kong, Squirrel Dude, Car Keys, etc.), places (Bed, Car, Inside, Outside, etc.), and people (e.g., Mum, Dad, Jamie, etc.).

The basic training sequence is always the same:

1. Request . 2. Lure. 3. Response . 4. Reward

This simple sequence is all that there is to the “science” of lure/reward training. After just half a dozen repetitions, the food lure is no longer necessary because the dog will respond to the hand-lure movement (hand signal). After twenty or so repetitions (with an half-a-second interval between the request and the hand signal), the dog will begin to anticipate the signal on hearing the request, i.e., the dog will respond immediately after the request but before the hand signal. The hand signal is no longer necessary, since the dog has now leaned the meaning of the verbal request.

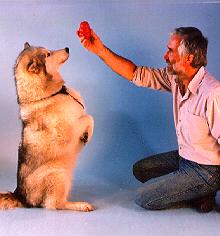

The “art” of lure/reward training very much depends on the trainer’s choice and effective use of an effective lure. The lure can be any item or action that reliably causes the dog to respond appropriately. Obviously, the trainer and the trainer’s body movements are the very best lures (and rewards), with interactive toys coming a close second. However, for pet owners, food is generally the best choice for both lures and rewards. Again, pet owners are not yet dog trainers, but they need to train their dog right away using the easiest and quickest technique.

Food lures should not be used for more than half a dozen trials. The prolonged use of the same item as both lures and rewards comes pretty close to bribing — wherein the dog’s response will become contingent on whether or not the owner has food in her hand. Either completely go cold turkey on food lures after just six trials, or use different items as lures and rewards. For example, use food to lure the dog to sit but a tennis ball retrieve as a reward. Or, use a hand signal to lure the sit but an invitation to the couch as a reward. Regardless of what you choose as lures and rewards, always commence each sequence with the verbal request.

For pet owners, dry kibble is the standard choice for both lures and rewards. Weigh out the daily ration each morning and keep it in a screw-top jar to be handfed as lures and rewards in the course of the day. Freeze-dried liver is reserved for special uses: rewards for housetraining, lures for chwtoys, lures for Shush, occasional lures and rewards for men and children to use, and for classical conditioning (to children, men, other dogs, motorcycles, and other scary stuff).

2.. Teaching The Dog To Want To Do What We Want Him To Do

Stage II involves phasing out training rewards as they are first replaced by life rewards and then eventually, by auto-reinforcement. Just because a dog “knows” what we want him to do does not mean to say that he will necessarily do it. Puppy responses are pretty predictable and reliable but with the advent of adolescence, most dogs become more independent and quickly develop competing interests, many of which become distractions to training. Given the choice between coming when called and sniffing another dog’s rear end, most adolescent dogs would choose the latter.

To maintain response reliability, all of the dog’s hobbies and competing interests must be used as rewards. Training must be completely integrated into the dog’s lifestyle. Training should comprise: short preludes before every enjoyable doggy activity (a la Premack) and numerous short interludes within every enjoyable long-term doggy activity. For example, the dog should be requested to sit before the owner puts on the leash, opens the back door, opens the car door, takes off the leash, throws a tennis ball, takes back the tennis ball, allows the dog to greet another dog or person, or offers a couch invitation or tummy rub. And of course, the dog should sit before the owner serves supper. Additionally, walks should be interrupted every 25 yards and play with other dogs should be interrupted every 15 seconds for a brief training interlude, (e.g., random position changes with variable length stays). Each interruption allows the resumption of walk or play to be used again as a life reward. As a cautionary note, if walks and play are not frequently interrupted, the puppy/adolescent will quickly learn to pull on leash and no doubt will become an uncontrollable social loon or bully.

Food rewards are no longer necessary for reliable performance, but it is smart to occasionally offer kibble rewards prior to life rewards during training preludes and interludes, so that the presentation (and eating) of kibble (an average-value primary reinforcer) becomes a mega secondary reinforcer. Supercharged kibble is useful when teaching subsequent exercises.

The ultimate goal in dog training is for the response to become the reward so that the dog becomes internally motivated and the response is auto-reinforced. This is similar to what happens when people are effectively taught to play tennis, dance, or ski; external rewards are no longer necessary.

3. . Enforcing Compliance Without Fear Or Force

Stage III involves teaching the dog that he must always respond promptly and appropriately by enforcing compliance without fear or force.

Just because a dog really, really, really wants to do what we want him to do does not mean to say that he will always do it. Internally motivated dogs usually have response reliabilities around 90%. I have always thought that dogs are pure existentialists — they revel in the here and now — and that squirrel, that dog’s rear end, or that little boy on a skateboard is right here, right now. In a flash, reliability goes down the toilet.

There are times when a dog simply must follow instructions to the letter. A pet dog requires an ultra-reliable emergency sit or down, a rock-solid stay, and a healthy respect for doorway or curbside boundaries. (Play Musical Chairs to achieve these skills quickly and enjoyably — see

K9 GAMES®.) Once we have used just about every conceivable life reward under the sun to internally motivate a dog to want to comply, we must also teach the dog that there are instances when he must comply.

In all the fields of dog training, enforcing compliance is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect. When discussing punishment, training tends to change from a science to a religionand some trainers express emotional extremes. Some trainers hold the view that compliance must be enforced by physical (often painful) punishments, such as leash corrections or electric shock, and other trainers abhor the use of punishment.

Regardless of where any trainer lies on the continuum of relative use of rewards and punishments:

1. Minor stressors are essential during early development for an animal to develop confidence as an adult, and certainly to develop sufficient confidence to live with humans. Learning, training, and development are often stressful. Adolescence is extremely stressful. It’s a simple fact of life.

2. It is essential to consider, “What to do when Plan A fails?” What to do when the dog dashes out of the front door and into the street to chase the boy on the skateboard? What is Plan B, or Plan C?

3. For the dog’s safety, compliance must be enforced to raise response-reliability to 95% (within two seconds after a single command) and to 100% (following Plan B or C)

Compliance may be effectively enforced without fear or force. Technically, a punishment decreases the frequency of the immediately preceding behavior and reduces the likelihood that it will occur in the future. A punishment need not be physical, painful, scary, aversive, or unpleasant. A punishment needs to adhere to eight criteria. Most important, punishments need to be effective (a tautology), instructive, and immediate, yet not overbearing.

Personally, I dislike using any gizmo or permanent management tool. Instead, I like to rely on the things that are always readily available: voice (for requests/commands, praise, and instructive reprimands), food and toys (as lures and rewards), and hands (for rewards and control). In those instances when the dog does not respond following a single command, the dog will eventually respond (100% of the time) after any number of instructive reprimands delivered in a negative reinforcement format.

Once a dog has been trained (exclusively via positive reinforcement) to 90% response reliability, whenever he fails to respond within two seconds, I instructively reprimand the dog — “Rover, Sit!” The volume of the instructive reprimand is lower than normal and the tone is soft and sweet…yet insistent. Once the dog sits, for example, I say “Thank you” and then the dog has to immediately repeat the exercise to meet the original criteria — to promptly sit following a single request. Once the dog sits within two seconds of a single request, I praise the dog, offer a couple of treats, and say “Go Play.” If the dog does not sit following the instructive reprimand, the instructive reprimand is repeated until the dog complies, whereupon the dog has to immediately repeat the exercise and meet criteria, before “life as the dog knows it” continues once more.

“Insistence” is the key word. Once you have instructed a dog to sit, calmly and sweetly insist that he does so. Once he sits, albeit eventually, and you now have his undivided attention, quickly back up and ask him to come and sit once more, so that he promptly and willingly sits following a single request before praising and releasing him.

4. Refining Performance Precision And Pizazz

Once response-reliability tops 95%, it is time to shape and differentially reinforce performance precision and pizazz. For example, fronts, finishes and stays are refined by improving attention, expression, and exact location (forwards/backwards, closer/away, etc.) and body position (e.g., five types of down stay). Recalls are progressively accelerated and heeling is fine-tuned by teaching speed-up and slow-down.

5. Protecting Performance Reliability And Precision

Stage IV requires a substantial time-commitment and so it is essential to “protect” the dog’s superior performance. Snazzy obedience is quickly destroyed when obedience commands — most commonly “Heel” and “Down” are used to control the dog in stressful situations, e.g., around dodgy dogs or people. Much worse is when obedience commands are misused by family and friends. For example, when a husband instructs five dogs to ”Sit Stay” at the front door, when admitting three buddies for pizza, beer and televised sports. One dog barks, one dog jumps up, one dog gooses the guest, one dog lies down (knowing that husbands don’t know the difference), and one dog sits and stays…and is forgotten. When the obedient dog eventually breaks his sit stay and creeps into the living room, he is rewarded by laughter and pizza for breaking his stay.

Training is best protected by having three command levels: DogCon One, DogCon Two, and DogCon Three. The dog is given a different cue, or perhaps easier — a different name for each command level: an informal pet name, a formal name, and a competition/working/demo name respectively. The choice of name informs the dog which level of obedience is required: the pet name prefix signifies a mere suggestion (which may be ignored), the formal name prefix requires 100% reliability, and the demo name calls for ultimate reliability, precision and pizazz. It’s showtime!

The notion of allowing a dog to ignore a command used to shock trainers. But this is what happens most of the time around the home anyway; giving commands and not enforcing the dog’s response is the major reason why reliability goes downhill. By acknowledging and formalizing “disobedience” and allowing a dog to ignore pet-name suggestions, we can better protect formal-name reliability. All we have to remember is that on those occasions when we use the formal-name prefix, we must insist on 100% compliance.

As T. S. Eliot might have said, “A dog should have three different names.”

Adapted from an article originally published in The Chronicle of the Dog — the Newsletter for the Association of Pet Dog Trainers (www.apdt.com)

©2006 Ian Dunbar

Other techniques are championed in other specialist training fields, wherein the syllabus is finite and the trainer knows the rules and questions (criteria) before the examination and especially, when time is not an issue—knowledgeable, experienced, and dedicated handlers will train for hours to perfect a desired behavior. However, pet dog training differs markedly from teaching competition or working dogs. With pet dog training, the questions are unknown and the syllabus is infinite — comprising all aspects of a dog’s (and owner’s) behavior, temperament, and training. But the most important difference by far — by and large owners are not dog trainers; they seldom have a trainer’s education, experience, or expertise.

Trainers should never underestimate their own expertise. Characteristically, techniques that we recommend for owners to train their dogs are entirely different (easier, quicker, and less complicated) than techniques that we might use to train our dogs.

In pet dog training, the two most expedient techniques are Lure/Reward Training and All-or- None Reward Training. This article describes a comprehensive lure/reward training program, which comprises five stages:

- Teaching The Dog What We Want Him To Do

- Teaching The Dog To Want To Do What We Want Him To Do

- Enforcing Compliance Without Fear Or Force

- Refining Performance Precision And Pizzazz

- Protecting Performance Reliability and Precision

The first three steps focus on establishing response reliability and are all-important in all fields of dog training. The last two steps — for refining precision and for protecting precision and reliability — are primarily for obedience, working, and demo dogs and will only be summarized in this article.

I. Teaching The Dog What We Want Him To Do

Stage I involves completely phasing out food lures as they are first replaced by hand signals (hand lures) and then eventually, by requests (verbal lures).

Given the prospect of the plethora of rewarding consequences for appropriate behavior, most dogs would gladly respect our wishes and follow our instructions, if only they could understand what we were asking. In a sense, Stage I involves teaching dogs ESL—English as a Second Language — teaching dogs the meaning of the human words that we use for instructions. Dogs need to be taught words for their body actions (Sit, Down, Stand, etc.), and activities (Go Play, Fetch, Tug, etc.), and for items (Kong, Squirrel Dude, Car Keys, etc.), places (Bed, Car, Inside, Outside, etc.), and people (e.g., Mum, Dad, Jamie, etc.).

The basic training sequence is always the same:

1. Request . 2. Lure. 3. Response . 4. Reward

This simple sequence is all that there is to the “science” of lure/reward training. After just half a dozen repetitions, the food lure is no longer necessary because the dog will respond to the hand-lure movement (hand signal). After twenty or so repetitions (with an half-a-second interval between the request and the hand signal), the dog will begin to anticipate the signal on hearing the request, i.e., the dog will respond immediately after the request but before the hand signal. The hand signal is no longer necessary, since the dog has now leaned the meaning of the verbal request.

The “art” of lure/reward training very much depends on the trainer’s choice and effective use of an effective lure. The lure can be any item or action that reliably causes the dog to respond appropriately. Obviously, the trainer and the trainer’s body movements are the very best lures (and rewards), with interactive toys coming a close second. However, for pet owners, food is generally the best choice for both lures and rewards. Again, pet owners are not yet dog trainers, but they need to train their dog right away using the easiest and quickest technique.

Food lures should not be used for more than half a dozen trials. The prolonged use of the same item as both lures and rewards comes pretty close to bribing — wherein the dog’s response will become contingent on whether or not the owner has food in her hand. Either completely go cold turkey on food lures after just six trials, or use different items as lures and rewards. For example, use food to lure the dog to sit but a tennis ball retrieve as a reward. Or, use a hand signal to lure the sit but an invitation to the couch as a reward. Regardless of what you choose as lures and rewards, always commence each sequence with the verbal request.

For pet owners, dry kibble is the standard choice for both lures and rewards. Weigh out the daily ration each morning and keep it in a screw-top jar to be handfed as lures and rewards in the course of the day. Freeze-dried liver is reserved for special uses: rewards for housetraining, lures for chwtoys, lures for Shush, occasional lures and rewards for men and children to use, and for classical conditioning (to children, men, other dogs, motorcycles, and other scary stuff).

2.. Teaching The Dog To Want To Do What We Want Him To Do

Stage II involves phasing out training rewards as they are first replaced by life rewards and then eventually, by auto-reinforcement. Just because a dog “knows” what we want him to do does not mean to say that he will necessarily do it. Puppy responses are pretty predictable and reliable but with the advent of adolescence, most dogs become more independent and quickly develop competing interests, many of which become distractions to training. Given the choice between coming when called and sniffing another dog’s rear end, most adolescent dogs would choose the latter.

To maintain response reliability, all of the dog’s hobbies and competing interests must be used as rewards. Training must be completely integrated into the dog’s lifestyle. Training should comprise: short preludes before every enjoyable doggy activity (a la Premack) and numerous short interludes within every enjoyable long-term doggy activity. For example, the dog should be requested to sit before the owner puts on the leash, opens the back door, opens the car door, takes off the leash, throws a tennis ball, takes back the tennis ball, allows the dog to greet another dog or person, or offers a couch invitation or tummy rub. And of course, the dog should sit before the owner serves supper. Additionally, walks should be interrupted every 25 yards and play with other dogs should be interrupted every 15 seconds for a brief training interlude, (e.g., random position changes with variable length stays). Each interruption allows the resumption of walk or play to be used again as a life reward. As a cautionary note, if walks and play are not frequently interrupted, the puppy/adolescent will quickly learn to pull on leash and no doubt will become an uncontrollable social loon or bully.

Food rewards are no longer necessary for reliable performance, but it is smart to occasionally offer kibble rewards prior to life rewards during training preludes and interludes, so that the presentation (and eating) of kibble (an average-value primary reinforcer) becomes a mega secondary reinforcer. Supercharged kibble is useful when teaching subsequent exercises.

The ultimate goal in dog training is for the response to become the reward so that the dog becomes internally motivated and the response is auto-reinforced. This is similar to what happens when people are effectively taught to play tennis, dance, or ski; external rewards are no longer necessary.

3. . Enforcing Compliance Without Fear Or Force

Stage III involves teaching the dog that he must always respond promptly and appropriately by enforcing compliance without fear or force.

Just because a dog really, really, really wants to do what we want him to do does not mean to say that he will always do it. Internally motivated dogs usually have response reliabilities around 90%. I have always thought that dogs are pure existentialists — they revel in the here and now — and that squirrel, that dog’s rear end, or that little boy on a skateboard is right here, right now. In a flash, reliability goes down the toilet.

There are times when a dog simply must follow instructions to the letter. A pet dog requires an ultra-reliable emergency sit or down, a rock-solid stay, and a healthy respect for doorway or curbside boundaries. (Play Musical Chairs to achieve these skills quickly and enjoyably — see

K9 GAMES®.) Once we have used just about every conceivable life reward under the sun to internally motivate a dog to want to comply, we must also teach the dog that there are instances when he must comply.

In all the fields of dog training, enforcing compliance is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect. When discussing punishment, training tends to change from a science to a religionand some trainers express emotional extremes. Some trainers hold the view that compliance must be enforced by physical (often painful) punishments, such as leash corrections or electric shock, and other trainers abhor the use of punishment.

Regardless of where any trainer lies on the continuum of relative use of rewards and punishments:

1. Minor stressors are essential during early development for an animal to develop confidence as an adult, and certainly to develop sufficient confidence to live with humans. Learning, training, and development are often stressful. Adolescence is extremely stressful. It’s a simple fact of life.

2. It is essential to consider, “What to do when Plan A fails?” What to do when the dog dashes out of the front door and into the street to chase the boy on the skateboard? What is Plan B, or Plan C?

3. For the dog’s safety, compliance must be enforced to raise response-reliability to 95% (within two seconds after a single command) and to 100% (following Plan B or C)

Compliance may be effectively enforced without fear or force. Technically, a punishment decreases the frequency of the immediately preceding behavior and reduces the likelihood that it will occur in the future. A punishment need not be physical, painful, scary, aversive, or unpleasant. A punishment needs to adhere to eight criteria. Most important, punishments need to be effective (a tautology), instructive, and immediate, yet not overbearing.

Personally, I dislike using any gizmo or permanent management tool. Instead, I like to rely on the things that are always readily available: voice (for requests/commands, praise, and instructive reprimands), food and toys (as lures and rewards), and hands (for rewards and control). In those instances when the dog does not respond following a single command, the dog will eventually respond (100% of the time) after any number of instructive reprimands delivered in a negative reinforcement format.

Once a dog has been trained (exclusively via positive reinforcement) to 90% response reliability, whenever he fails to respond within two seconds, I instructively reprimand the dog — “Rover, Sit!” The volume of the instructive reprimand is lower than normal and the tone is soft and sweet…yet insistent. Once the dog sits, for example, I say “Thank you” and then the dog has to immediately repeat the exercise to meet the original criteria — to promptly sit following a single request. Once the dog sits within two seconds of a single request, I praise the dog, offer a couple of treats, and say “Go Play.” If the dog does not sit following the instructive reprimand, the instructive reprimand is repeated until the dog complies, whereupon the dog has to immediately repeat the exercise and meet criteria, before “life as the dog knows it” continues once more.

“Insistence” is the key word. Once you have instructed a dog to sit, calmly and sweetly insist that he does so. Once he sits, albeit eventually, and you now have his undivided attention, quickly back up and ask him to come and sit once more, so that he promptly and willingly sits following a single request before praising and releasing him.

4. Refining Performance Precision And Pizazz

Once response-reliability tops 95%, it is time to shape and differentially reinforce performance precision and pizazz. For example, fronts, finishes and stays are refined by improving attention, expression, and exact location (forwards/backwards, closer/away, etc.) and body position (e.g., five types of down stay). Recalls are progressively accelerated and heeling is fine-tuned by teaching speed-up and slow-down.

5. Protecting Performance Reliability And Precision

Stage IV requires a substantial time-commitment and so it is essential to “protect” the dog’s superior performance. Snazzy obedience is quickly destroyed when obedience commands — most commonly “Heel” and “Down” are used to control the dog in stressful situations, e.g., around dodgy dogs or people. Much worse is when obedience commands are misused by family and friends. For example, when a husband instructs five dogs to ”Sit Stay” at the front door, when admitting three buddies for pizza, beer and televised sports. One dog barks, one dog jumps up, one dog gooses the guest, one dog lies down (knowing that husbands don’t know the difference), and one dog sits and stays…and is forgotten. When the obedient dog eventually breaks his sit stay and creeps into the living room, he is rewarded by laughter and pizza for breaking his stay.

Training is best protected by having three command levels: DogCon One, DogCon Two, and DogCon Three. The dog is given a different cue, or perhaps easier — a different name for each command level: an informal pet name, a formal name, and a competition/working/demo name respectively. The choice of name informs the dog which level of obedience is required: the pet name prefix signifies a mere suggestion (which may be ignored), the formal name prefix requires 100% reliability, and the demo name calls for ultimate reliability, precision and pizazz. It’s showtime!

The notion of allowing a dog to ignore a command used to shock trainers. But this is what happens most of the time around the home anyway; giving commands and not enforcing the dog’s response is the major reason why reliability goes downhill. By acknowledging and formalizing “disobedience” and allowing a dog to ignore pet-name suggestions, we can better protect formal-name reliability. All we have to remember is that on those occasions when we use the formal-name prefix, we must insist on 100% compliance.

As T. S. Eliot might have said, “A dog should have three different names.”

Adapted from an article originally published in The Chronicle of the Dog — the Newsletter for the Association of Pet Dog Trainers (www.apdt.com)

©2006 Ian Dunbar